Zero temperature

Exact diagonalization study of long-range interactions in quantum lattice models at zero temperature.

In late 2018, I started my Ph.D. investigating the fundamental question of how long-range interactions impact the physics in strongly correlated systems. As with any complicated project, my advisors and I needed a (relatively) controlled starting point into order to begin answering the smaller, more concrete questions contained within the framework of our work. This entailed fixing the dimensionality and lattice geometry that we wanted to investigate, as well as simplifying other degrees of freedom.

With the quarter-filled organic salt family, \(\theta\)-ET\(_{2}\)X as our inspiration, we decided to study a triangular lattice system with only charge degrees of freedom. The quarter-filling and the prohibitive cost for any two particles to share a site justified our deliberate choice to neglect the spin degrees of freedom.

These choices enabled us to write down the following Hamiltonian in second quantization to describe the energetic processes underlying our system:

\begin{equation}\label{eq:long-range-Hamiltonian} H = -t \sum_{\langle ij \rangle} \big( \hat{c}^{\dagger}_{i} \hat{c}_{j}^{} + h.c. \big) + \frac{V}{2} \sum_{ij} \frac{ ( \hat{n}_{i} - \bar{n} )( \hat{n}_{j} - \bar{n} ) }{ R_{ij} }. \end{equation}

The first term details the kinetic energy which the system gains by means of “hops” between nearest-neighbor sites. The second term describes the electrostatic interactions of a configuration of charges where the parameter \(\alpha\) controls the range of the interactions. The value \(\alpha=1\) corresponds to the pure, unscreened Coulomb repulsion and \(\alpha \rightarrow \infty\) corresponds to the limit with only nearest-neighbor interactions.

With this Hamiltonian established, we employed a technique called exact diagonalization to examine the ground state of the system as a function of the interaction range, interaction strength, and system size. This technique is quite common in condensed matter physics and consists of diagonalizing a matrix corresponding to the Hamiltonian computed for a given basis of states.

In our case, we fixed the size of the system (the number of sites on the lattice) and established the basis of states by considering all possible charge configurations for a half-filled spinless system. For each state (charge configuration), we fill in the appropriate elements of the Hamiltonian matrix that correspond to the electrostatic interactions (diagonal elements) and the kinetic hopping processes (off-diagonal elements). Finally, the matrix is diagonalized and any observables of interest, such as charge correlation, are computed to provide insight into the nature of the ground state.

Exact diagonalization is a powerful technique as it provides microscopic control over all parameters and accounts for all of the electronic correlation. However, it is limited to small system sizes as the basis size, and thereby the computational cost, grows exponentially with the system size. As we are forced to work with relatively small system sizes, we additionally needed to employ two strategies designed to minimize finite-size effects–twisted boundary conditions and Ewald summations. A more detailed explanation of these highly technical points can be found in my dissertation, but for the present discussion, it suffices to say that twisted boundary conditions and Ewald summations reduce finite-size errors arising from the kinetic and potential terms of the Hamiltonian, respectively.

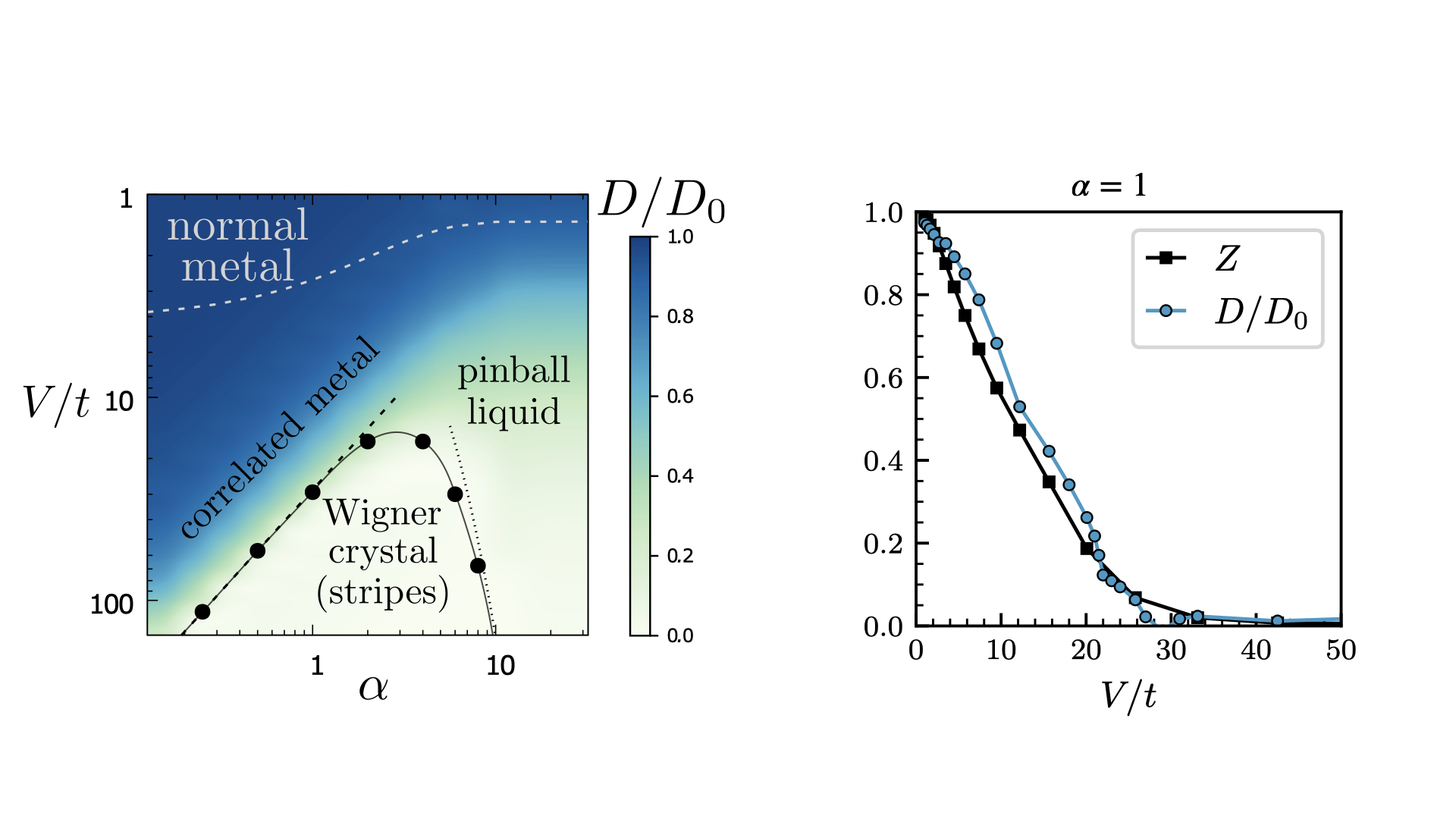

With the technical points resolved, we can now turn our attention to the results obtained by diagonalizing the Hamiltonian in Eq. \eqref{eq:long-range-Hamiltonian}. First, we establish the phase diagram by computing the Drude weight as a function of varying interaction range and strength. The Drude weight characterizes the charge stiffness in a system and can be used to classify metallic or insulating regions in the phase diagram.

Across all values of interaction range \(\alpha\), we observed a “normal” metal for low values of interaction strength, \(V/t\). This corresponds to the top, dark blue region of the phase diagram in the left panel above. We also found that as the interaction strength is increased in systems with short-range interactoins, then this normal metal transitions into a phase known as the pinball liquid (righthand side of left panel). This phase corresponds to a splitting of the electronic density into one portion that is “pinned” to the lattice and another portion that flows over the remaining lattice sites (“balls”). As this phase only occurs for short-ranged interactions and has been the subject of other studies, we shall not concern ourselves any further with it.

Instead, we shall focus our attention on the case of pure, Coulomb long-range interactions which corresponds to the case \(\alpha=1\). As can be seen in the phase diagram above, the normal metal transitions instead to a correlated metal as the interaction strength is increased. Eventually, the repulsive nature of the electronic interactions completely dominates the kinetic processes and the system settles into a stripe-ordered, insulating phase. This phase is also called a Wigner crystal as it arises from long-range interactions. The right panel of the figure above shows not only the decrease of the Drude weight at the approach of the metal-insulator transition, but also that of the quasiparticle weight. Both quantities, although computed in different ways from the diagonalization, agree well and signal that the electronic correlation is building up with the increase in interaction strength, \(V/t\).

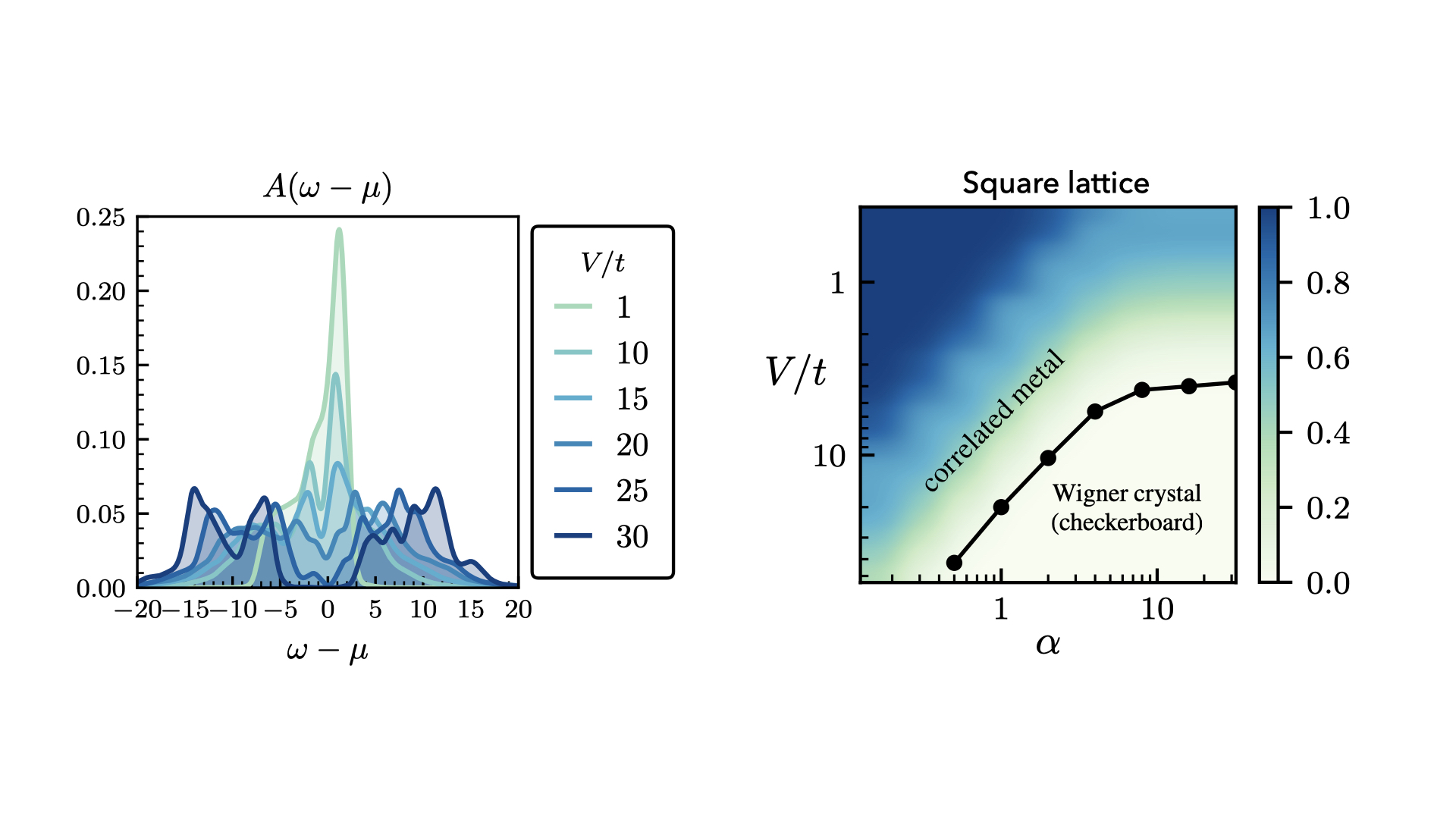

Another quantity that provides us with a measure of electron correlation is the single-particle spectral function, \(A(\omega)\). This quantity is shown in the figure below and we clearly observe the development of a pseudogap as the interaction strength \(V/t\) increases to its value at the metal-insulator transition, \((V/t)_{c} \approx 30\).

At this point, it is worth pointing out that our discovery of a correlated metallic phase also holds on lattices that are not geometrically frustated. This can be seen in the phase diagram of our model computed on the square lattice, shown below in the right panel. For the long-range interactions, we clearly see a transition from normal metallic state to correlated metal before finally undergoing an insulating transition. However, this transition occurs for a lower value of \(V/t\), thereby suggesting that the geometric frustration of the triangular lattice enhances the frustrating effects of long-range interactions in the build-up to the metal-insulator transition.

The presence of a pseudogap in the spectral function is remniscient of the Efros-Shklovskii Coulomb gap in classical systems. In the original 1975 paper, the authors (for whom the Coulomb gap is named) demonstrated that the density of states is suppressed around the Fermi level in classical systems with quenched disorder and long-range interactions. Almost two decades later, however, Efros put forth that the presence of disorder is not necessary to observe this pseudogap phenomenon and that the presence of long-range interactions is sufficient.

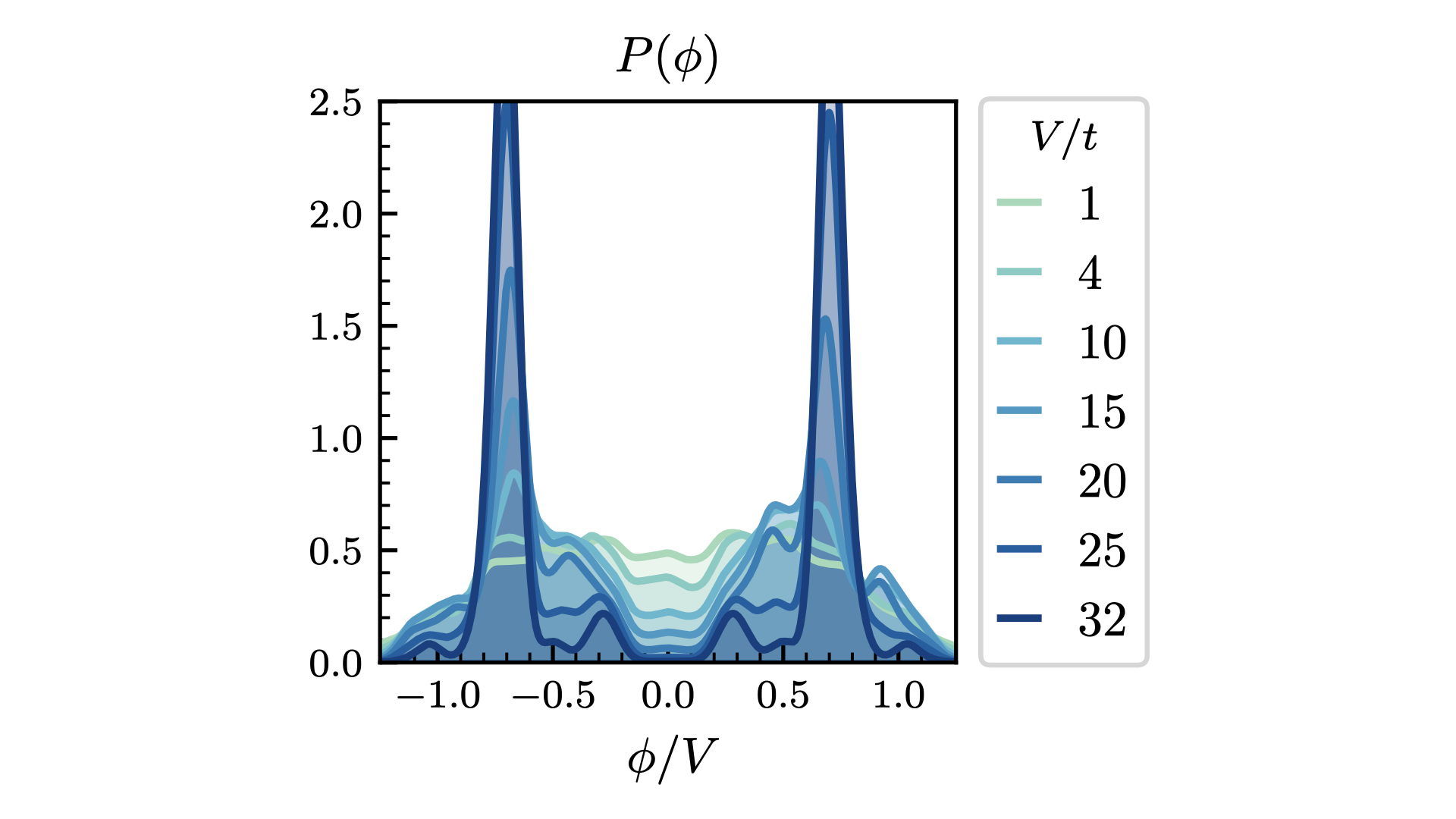

To determine if a similar mechanism could explain the presence of the pseudogap observed in our data, we constructed a quantum analogue of the distribution of electrostatic on-site potentials. We defined this quantity as

\begin{equation} P( \phi_{i} ) = \Bigg\langle \psi_{0} \Bigg\vert \delta\Bigg( \phi_{i} - \sum_{j \neq i} V( R_{ij} )( \hat{n}_{j} - \bar{n} ) \Bigg) \Bigg\vert \psi_{0} \Bigg\rangle. \end{equation}

In other words, \(\phi_{i}\) represents the electrostatic potential felt by an electron at site \(i\) from all of the other electrons in the system. When we studied this distribution as a function of the interaction strength leading up to the metal-insulator transition, we discovered a similar suppression of energy levels at the approach of the transition.

For the first time, we were able to demonstrate that long-range interactions act as a source of self-generated disorder in quantum systems, giving rise to novel correlated behavior. Additionally, we examined the spectrum of collective charge fluctuations, \(D( \omega )\). This quantity provides us with an understanding of the time required for a global rearrangement of the charges to occur. We learned that the long-range interactions and the disordered electrostatic landscapes that they create lead to slow collective charge fluctuations, or rearrangements.

We further hypothesized that the slow nature of these charge fluctuations could lead to the observation of anomalous transport at finite temperatures. Indeed, this became the focus of the second project of my Ph.D. and is discussed in the “Anomalous transport” section of the Projects page.