General introduction

Motivation for studying long-range interactions in condensed matter lattice models (aka my thesis topic)

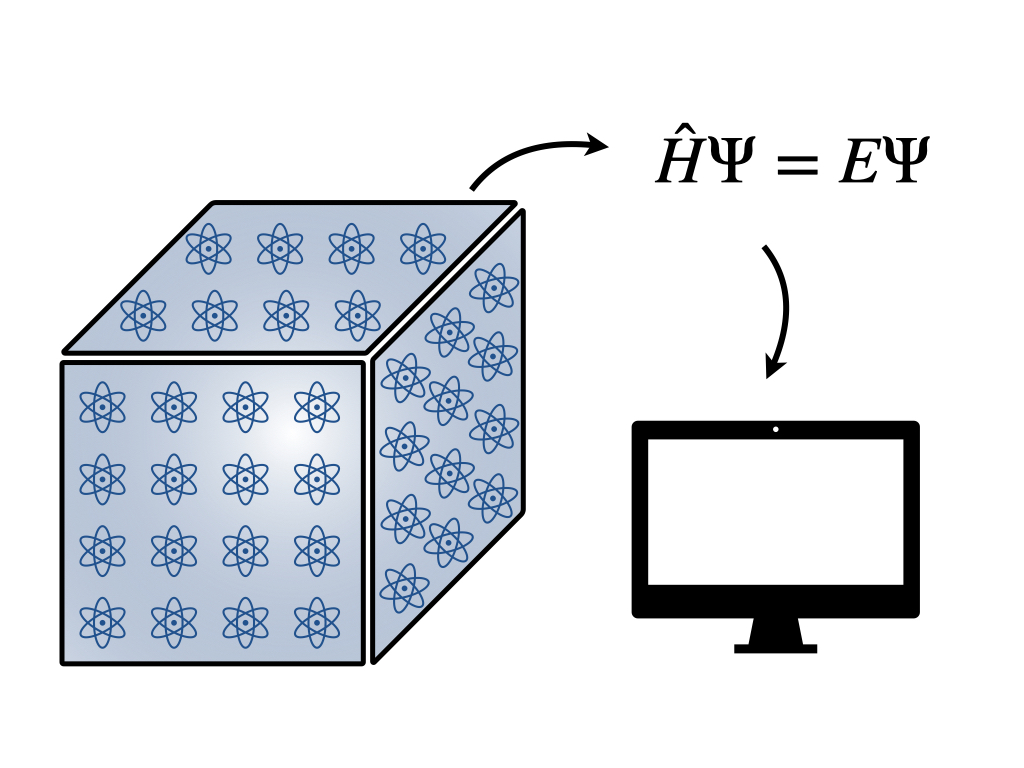

One of the main focuses of condensed matter physics is understanding the behavior of electrons in solids and ways in which emergent electronic behavior can be harnessed to develop new technologies, such as quantum computers, semi-conductor devices and phase change memory materials. When we first approach this problem, we have to think about the arrangement and interactions of electrons in solids. Typically, solids have a periodic arrangement of atoms and the valence (or outermost) electrons control the electronic properties of the system, as depicted below.

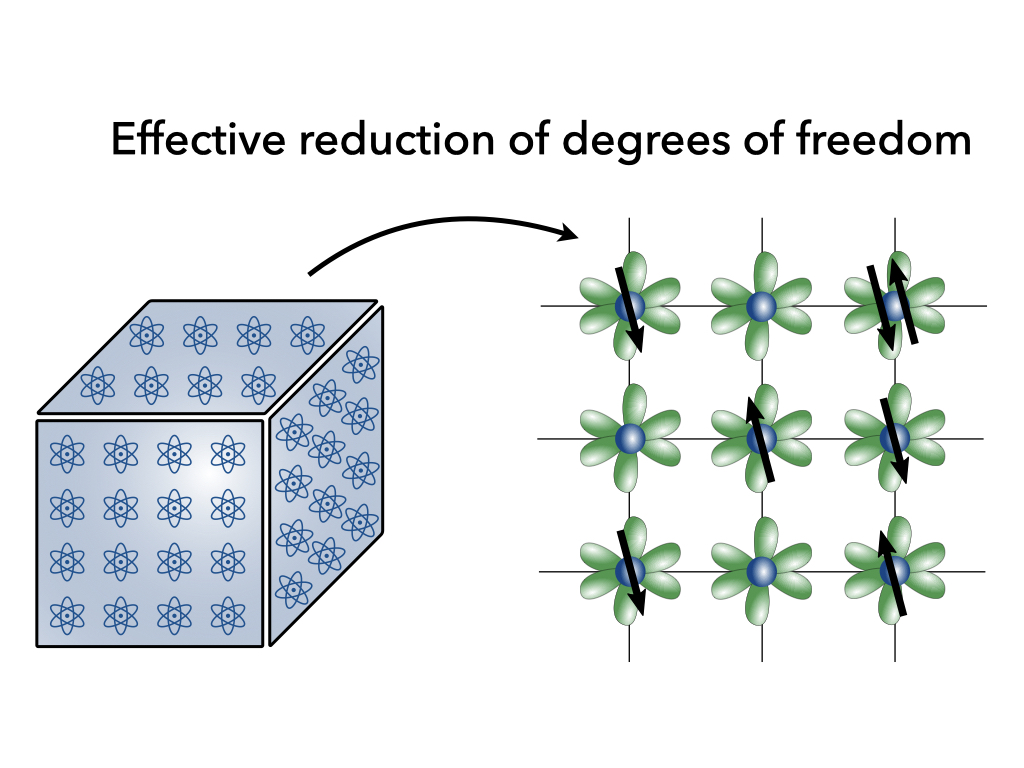

There are two different approaches to studying electronic solids in theoretical condensed matter physics. Ab-initio calculations attempt to solve the Schrodinger equation from first principles, i.e. by not including any experimentally-determined parameter values. These techniques tend to work very well for describing weakly correlated systems. While the development and application of these ab-initio methods constitutes an entire domain that is interesting in its own right, my dissertation work focused on the other main approach to studying electronic behavior: effective lattice models.

As the name suggests, the lattice is dictated by the underlying periodic arrangement of atoms in the solid and the most relevant degrees of freedom are said to “live” on the lattice. These degrees of freedom are typically the electron orbitals corresponding to the valence electrons and provide an effective representation of the physics at hand. These models are frequently implemented to study strongly correlated systems, where even a few degrees of freedom can lead to puzzling behavior.

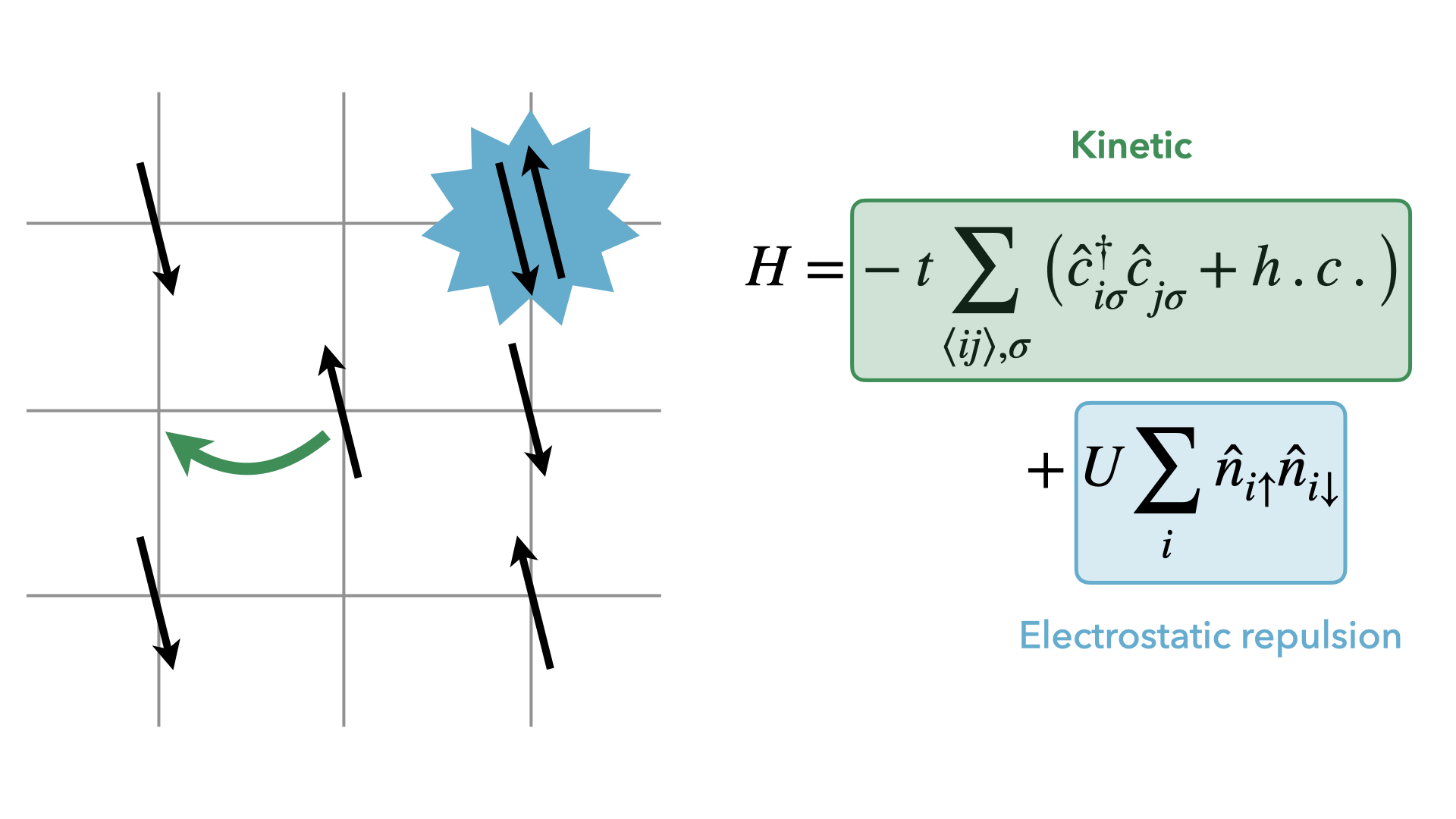

The Hubbard model is arguably the best known effective lattice model in condensed matter and its Hamiltonian in second quantization form is:

\begin{equation}\label{eq:Hubbard-Hamiltonian} H = -t \sum_{\langle ij \rangle, \sigma} \big( \hat{c}_{i\sigma}^{\dagger} \hat{c}_{j\sigma}^{} + h.c. \big) + U \sum_{i} \hat{n}_{i\uparrow} \hat{n}_{i\downarrow} \end{equation}

The first term describes the kinetic energy gained as an electron jumps from one site to any of its nearest neighbor sites and the second term describes the potential energy cost incurred when two electrons share the same lattice site. This is the simplest model of electron correlation and has helped to explain the correlation-based mechanisms behind metal-insulator transitions, notably the Mott metal-insulator transition. Furthermore, it is often used as a starting point to describe anomalous phases found in the vicinity of correlated insulators.

However, this model is only exactly solvable in one-dimensional systems (\(d=1\)) which has led to the development of numerical techniques capable of describing electronic correlation in higher dimensions (\(d=2,3\)). An excellent comparison of many state-of-the-art techniques applied to the single-orbital Hubbard model on the square lattice can be found in this article.

One of the key assumptions underlying the Hubbard model is that screening effects are so strong that electrons will only interact with one another if they share the same lattice site (second term of Eq. \eqref{eq:Hubbard-Hamiltonian}). This is also referred to as an “on-site” potential. Some studies, however, also consider the case when interactions extend to the nearest-neighbor sites. In these cases, the on-site interaction is typically governed by the \(U\) term from the Hubbard model (Eq. \eqref{eq:Hubbard-Hamiltonian} above) and the nearest-neighbor interaction is controlled by an additional term,

\begin{equation} V \sum_{\langle ij \rangle} \hat{n}_{i} \hat{n}_{j} \end{equation}

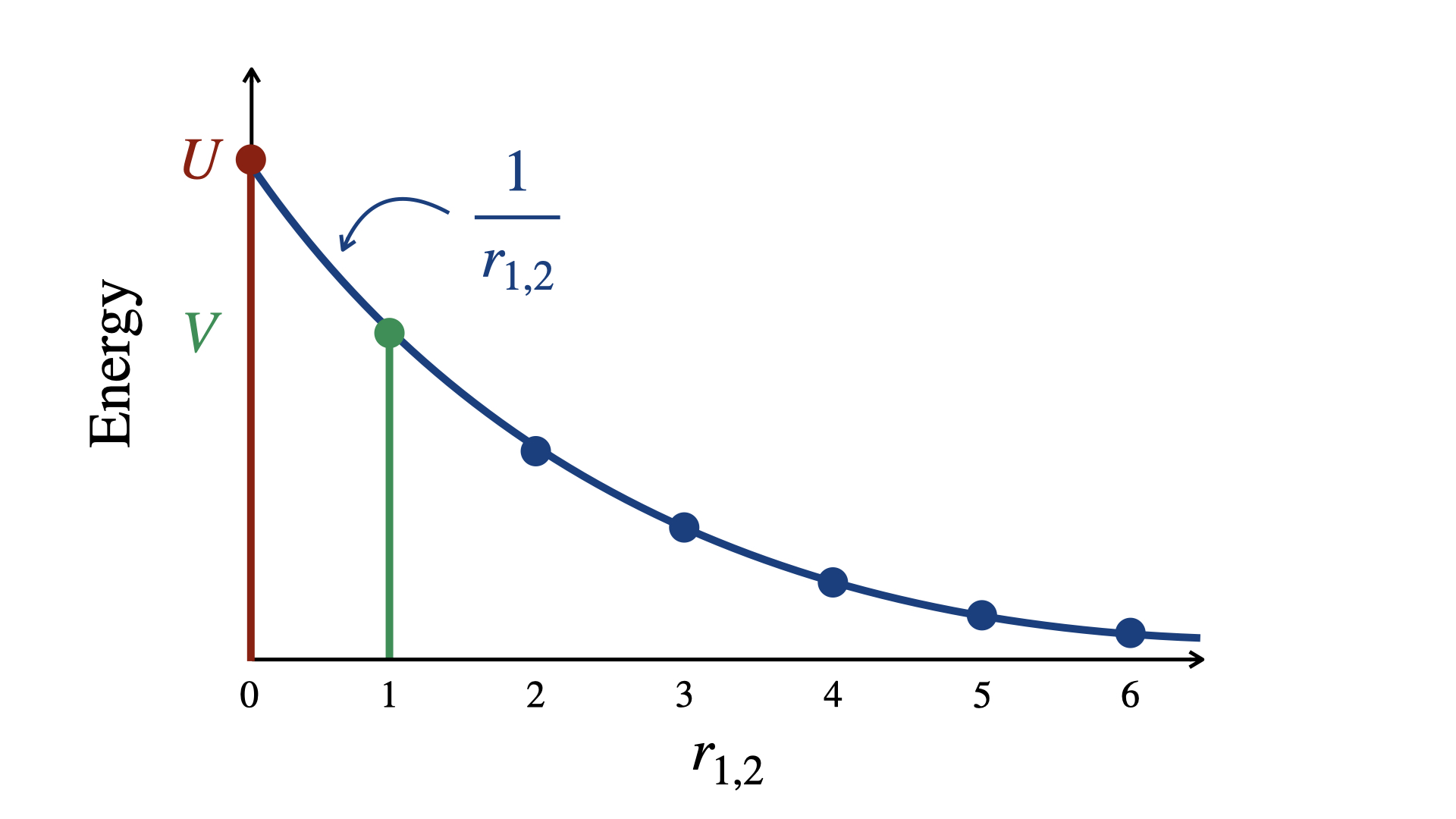

where \(V\) describes the interaction strength and \(\sum_{\langle ij \rangle}\) restricts the expression to nearest-neighbor sites, \(i\) and \(j\). Little is known, however, about what occurs when screening is very weak. We know from our high school science classes that the electrons interact via the Coulomb repulsion, which is a long-range interaction that decays as the distance between two particles increases.

\begin{equation} E = \frac{q_{1}q_{2}}{r_{1,2}} \end{equation}

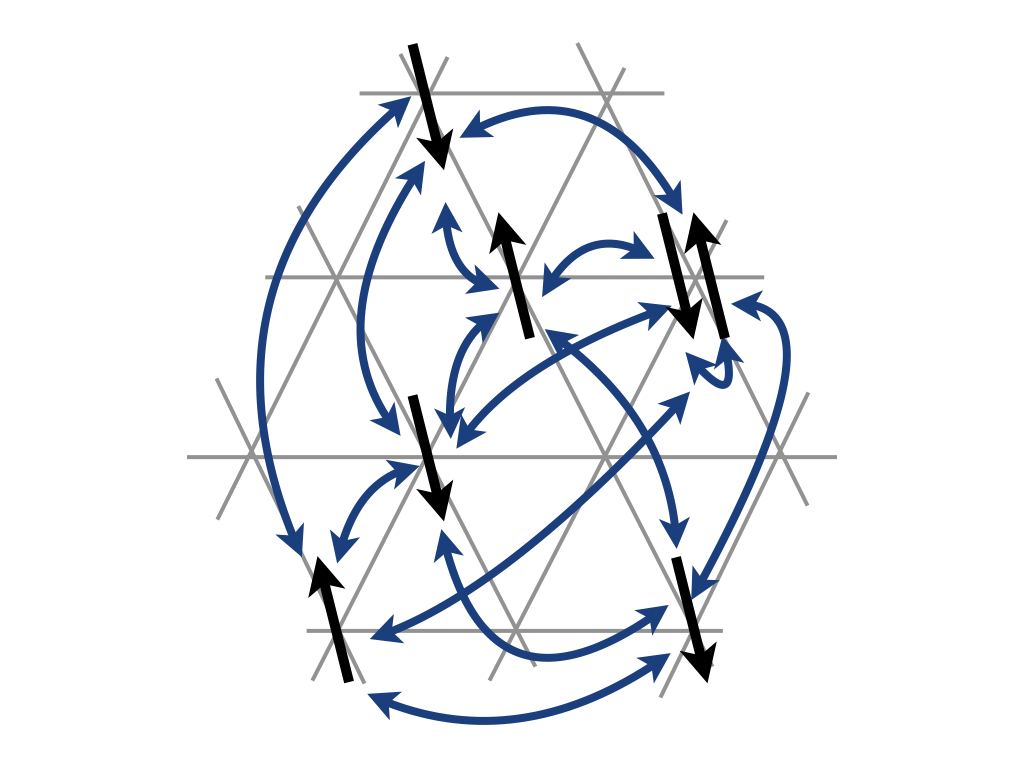

In the above equation, \(q_{i}\) signifies the charge of each particle and \(r_{1,2}\) the interparticle distance. The various forms of interactions are summarized in the figure below.

As one can immediately see above, considering only on-site or nearest-neighbor interactions in the case of poorly screened systems misses a large chunk of interactions. This large chunk of interaction contributions corresponds to all of the blue circles for \(r_{1,2} \geq 2\). While each individual contribution is not larger than that of the on-site or nearest-neighbor terms, the summation of these extended contributions winds up being quite large.

This begs the rather fundamental question: what happens when we properly account for these long-range interactions? More specifically, the questions that we addressed throughout the course of my thesis were:

- What do we know about the electronic properties and correlations arising from long-range interactions?

- Are they different from those that arise in conventional metals?

- Can they perhaps provide insight into unexplained phenomena?

Even before delving into the results, which are explained in other pages in my projects section, we can be fairly confident that we will discover novel behavior because we know that long-range interactions should act as a source of a frustration.

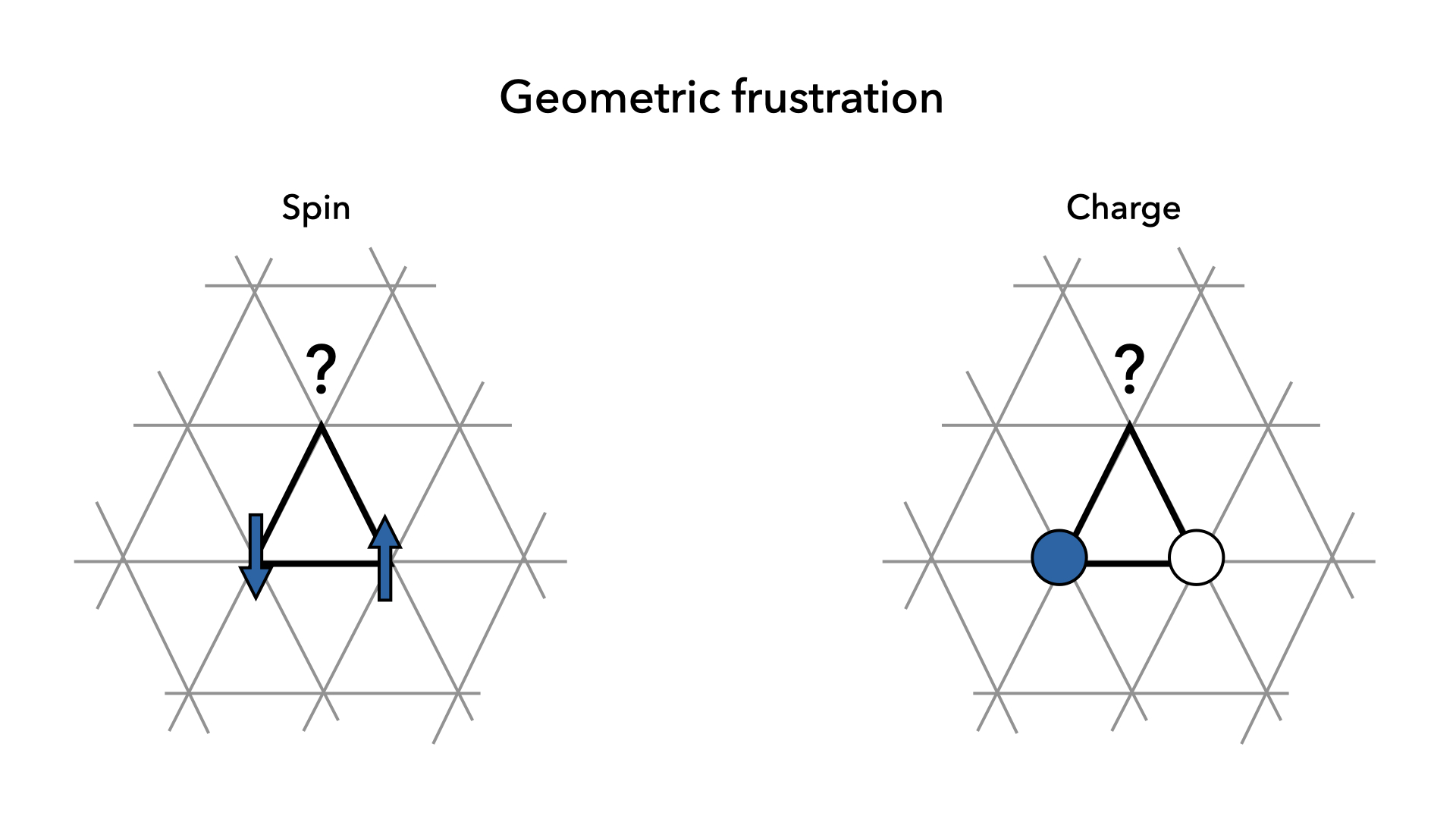

In condensed matter, the concept of frustration is often thought of in terms of spin frustration. Let us consider, for example, Ising spins that want to align antiferromagnetically on a two-dimensional triangular lattice. If we place spins on the sites (or vertices) of the unit cell, we see that we can place a spin-up and a spin-down on two different sites, but the third site is said to be frustrated as neither spin-up nor spin-down will satisfy the desired antiferromagnetic alignment.

Similarly, this frustration can occur with electronic charges when we replace the spin-up site with a charge-rich site, and the spin-down site with a charge-poor site. The third, remaining site does not know whether it should be charge-rich or charge-poor in order to minimize the repulsive electrostatic interactions, a phenomenon known as charge frustration.

However, when we properly account for long-range interactions, every electron interacts with every other electron in our system. Thus, the coordination of all of the particles in the system inherently frustrates the system. This non-local interaction picture is fundamentally different from the Hubbard model and should give rise to interaction-driven frustration.

Personally, I find this easiest to understand by thinking about having to plan a dinner. If you only have to plan for yourself, or perhaps your significant other, then it should a relatively simple task. However, if you have to plan a dinner for your entire extended family, then it starts to get frustrating as you have to consider all of the personal histories and interactions between different family members.